This Brutal Gangster Classic With 100% on Rotten Tomatoes Changed the Genre Forever

The Big Picture

-

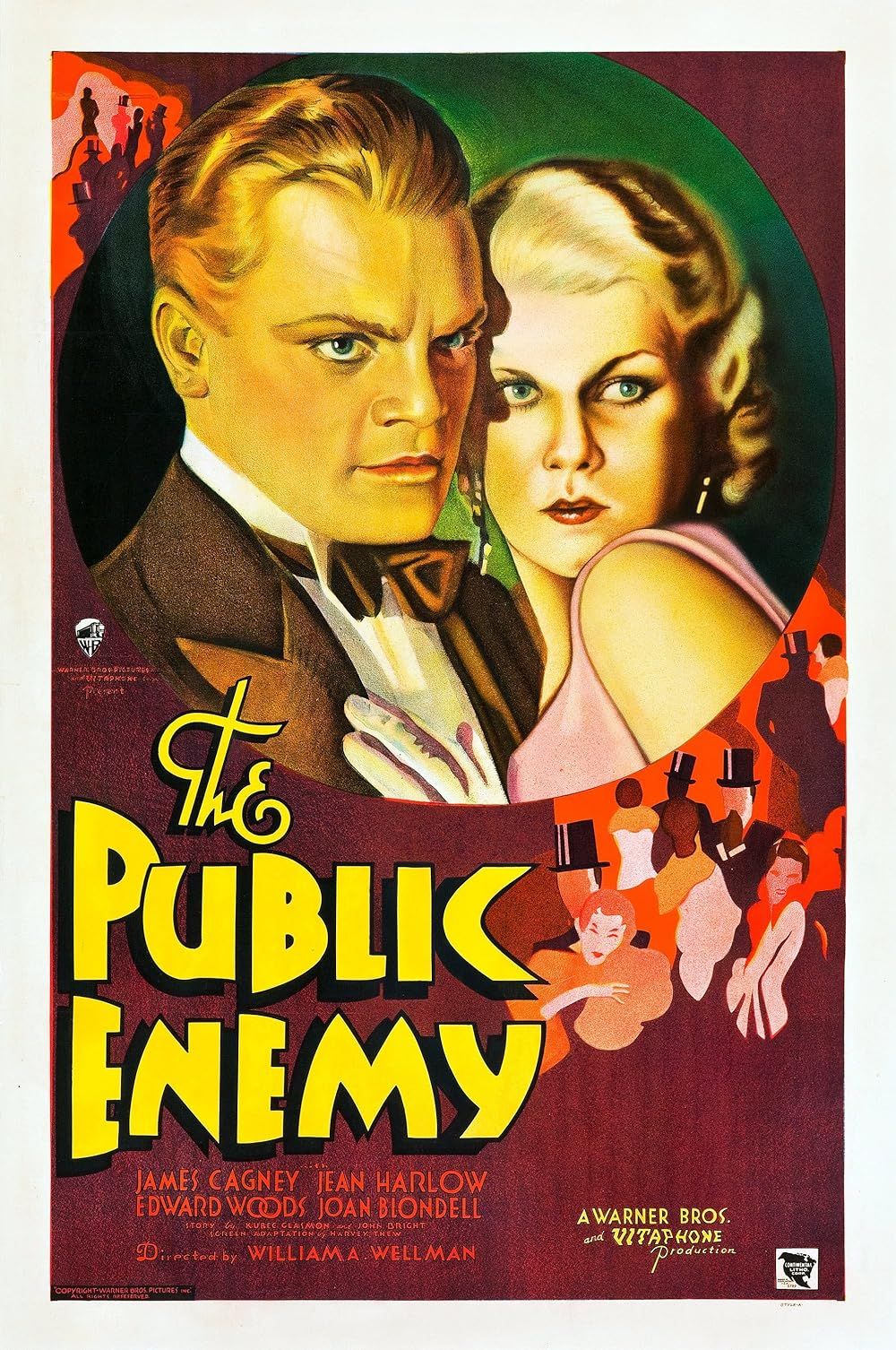

The Public Enemy

shaped the gangster genre, inspiring modern day classics like

The Godfather

and

The Sopranos

. - The film’s unflinching violence was a hallmark of pre-Code Hollywood, depicting crime with raw authenticity.

- Martin Scorsese drew inspiration from

The Public Enemy

, cementing its legacy in cinema.

Nearly 100 years considering the fact that its release, The Public Enemy‘s influence reigns supreme more than modern day cinema. The classic Pre-Code gangster film was a groundbreaking advancement of the film medium that paved the way for its genre. Produced by Warner Bros. and starring the seminal Hollywood hard guy James Cagney, The Public Enemy is a totemic image of the gangster genre. Without it, modern day audiences would have been deprived of titanic figures in the crime genre, like the films of Martin Scorsese and The Sopranos. The 1931 film, directed by old Hollywood staple, William A. Wellman, showed that crime wasn’t fairly, and any attempts to sanitize the criminal underworld are a disservice to reality and audience expectations. Critically lauded back then and nowadays, it was also the initially film to recognize that, deep down, in spite of our moral compass, we all romanticize gangsters.

The Public Enemy

An Irish-American street punk tries to make it massive in the globe of organized crime.

- Release Date

- April 23, 1931

- Director

- William A. Wellman

- Cast

- James Cagney , Jean Harlow , Joan Blondell

- Runtime

- 83

- Main Genre

- Crime

Pre-Code Hollywood Depicted Sex and Violence on the Big Screen

The Public Enemy follows Tom Powers (Cagney), a low-level petty thief who rises to the best of the bootlegging underworld in Prohibition-era Chicago along with his companion-in-crime, Matt Doyle (Edward Woods). Tom’s brother, Mike (Donald Cook), is an upstanding citizen and WWI veteran who denounces his brother’s illicit way of life. Tom engages in two romantic relationships: 1 with Kitty (Mae Clarke), and the other with Gwen Allen (Jean Harlow). In a brisk 83 minutes, The Public Enemy distills the gangster genre with distinct clarity. Currently sitting at 100% on Rotten Tomatoes, the film’s pristine, tight-as-a-drum narrative mirrors the dynamic arc of an aspiring gangster. With just 1 break, Tom Powers is at the best. Instantaneously, inside seemingly no time, Tom finds himself gunned down and in a hospital bed.

The film, with its unflinching violence and a narrative told by means of the eyes of an antihero, could only have existed through Hollywood’s pre-Code era. During this era, starting with the advent of sound in film in the late 1920s and ending with the enforcement of the Hays Code in 1934, studio images routinely featured violence, mild profanity, sexual innuendos, promiscuity, and infidelity. While this period was very best identified for its female liberation, signified by sex-optimistic films such as Baby Face and Red-Headed Woman, Pre-Code Hollywood helped make the iconography of the classic gangster. Amid Prohibition and the reign of Al Capone, Hollywood capitalized on the notoriety by portraying gangsters as modern day-day Western cowboys in films such as Little Caesar, Scarface, and The Public Enemy. The two faces of Pre-Code gangster films, Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney, had been shockingly depicted as noble Robin Hood-like figures — a thing Hollywood would modify following the adoption of the Hays Code by insisting that crime under no circumstances pays.

‘The Public Enemy’ Established the Modern Gangster Film

Cagney’s Capone-inspired Tom Powers is the quintessential Pre-Code gangster. He begins from practically nothing, but he swiftly attains energy and begins a turf war in between a rival gang. He is charismatic, proud of his wealth, and defies authority. Every iconic mobster efficiency in its wake, like Marlon Brando and Robert De Niro as Vito Corleone in The Godfather and The Godfather: Part II, and Al Pacino as Tony Montana in the <em>Scarface </em>remake, is indebted to Cagney, who balances the romanticism and sheer menace of organized crime. The verisimilitude of his efficiency complements Wellman’s challenging-boiled path. The Public Enemy does not just restrict the violence in between fellow mobsters, as maybe the most iconic and studied scene in the film is in domestic life. Demanding a drink, Tom verbally attacks Kitty at the table. Suddenly, following she tends to make a dismissive remark, Tom gets up and stuffs a grapefruit in her face. The sequence, an unglamorous show of domestic violence, was believed to be improvised. In reality, the scene was coordinated by Cagney and Mae Clarke as a sensible joke. Not in the original script, Wellman decided to leave the grapefruit scene in the final reduce.

Rather than their depiction of sex and violence, pre-Code Hollywood films had been additional provocative for the concepts they expressed. In the early ’30s, it was radical to depict a lady with private autonomy who worked her way up the corporate ladder when refusing to be monogamous. Running concurrently with the era’s feminist liberation is the depiction of gangsters as noble outlaws in the context of American ideology. The overarching dramatic theme of the film is the divide in between Tom and his brother, Mike, who rejects his brother’s blood funds. Before going off to fight in World War I, Mike tries to convince Tom to escape his life of crime, but by the time he returns property, Tom has evolved from a petty thief to a premier bootlegger. Rather than glorify Mike, the former Marine, the film identifies Tom as a noble go-getter. He’s not blinded by patriotism like his brother, but rather, he stays property to participate in American capitalism. The adage “crime doesn’t pay” is nowhere to be identified in The Public Enemy, as Tom creates a prosperous criminal enterprise as a bootlegger. Similar to Michael Corleone’s (Al Pacino) speech about the thin line in between politicians and gangsters in The Godfather, Tom argues that Mike, who killed Germans overseas in WWI, is a hypocrite, claiming he has no ideal to take the moral higher ground more than his gangster brother.

2:35

One of Robert De Niro’s Greatest Gangster Films Is Also His Most Personal

“You just have to accept people for what they are.”

How ‘The Public Enemy’ Inspired Martin Scorsese and ‘The Sopranos’

Growing up in the neighborhood of Manhattan, Little Italy, the criminal underworld was aspect of the ecosystem surrounding Martin Scorsese, which gave his iconic gangster films Mean Streets and Goodfellas a private touch. Scorsese, the ultimate cinephile, nevertheless employed inspiration from classic gangster images when directing Goodfellas, now regarded as the definitive portrayal of the mafia. Citing it as the initially gangster film he ever saw, Scorsese admired the “truthfulness” of The Public Enemy. He rejects the notion that Wellman’s path is “crude,” and as an alternative, celebrates its candor in expressing the plight of blue-collar Americans and how a want to make ends meet by means of illicit suggests “goes out of control.” Goodfellas is celebrated for its capacity to portray its subjects as likable persons you’d want to hang about with. While lots of viewers implore Scorsese to explicitly condemn his characters’ actions, depicting violent criminals as affable persons is a comment on the romanticism of organized crime in society. The Public Enemy highlights the luxuries of crime and an untapped insight into America, permitting the audience to come to be transfixed by the mob.

If Goodfellas defined organized crime on the massive screen, The Sopranos redefined it for the 21st century on cable. Compared to the clear lineage from The Public Enemy to Scorsese’s film, the series envisioned a unique sort of mobster, 1 whose neurosis was as significantly of a danger to him as rival gangsters or the FBI. Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) with his depressive worldview and troubled upbringing at the hands of his domineering mother, Livia (Nancy Marchand), stripped away the exciting and glamor of getting a sensible guy. Even with this postmodern take on the genre, The Sopranos paid tribute to the classics, and Tony himself was fond of the old films commonly played on Turner Classic Movies. In the book, The Sopranos Sessions, showrunner David Chase cited The Public Enemy as an early influence.

In Season 3, Episode 2, “Proshai, Livushka,” Tony intermittently watches The Public Enemy on Television. The episode centers about the death of Livia and her wake. At the finish of the episode, Tony watches the scene when Tom’s mother prepares for her son’s return property from the hospital. However, Tom under no circumstances returns property, as he is killed by a rival gang. Tony is brought to tears at the sight of an affectionate mother caring for her gangster son, a thing he under no circumstances skilled. At initially, Tony watches the film with glee, as Cagney and classic gangster films evoke an era of “strong, silent types” that he regularly bemoans the loss of in modern society. After a evening of grieving more than his difficult mother, this film, a supply of comfort meals, requires a melancholic turn. Deep down, he’s not jealous that he could not reside in Cagney’s time that disregarded mental overall health and therapy. He’s jealous that he did not have a loving mother.

Don’t dismiss The Public Enemy due to its age. If you watch it, you will understand how significantly of the gangster genre cribs from the classic James Cagney film. You do not have to be an aficionado of the genre to admire the William Wellman film, as its lurid power and vibrant portrait of crime represent the energy of Pre-Code cinema. The very best gangster films and shows, The Godfather, Goodfellas, and The Sopranos, present an intoxicating globe of crime and mischief. Whether we want to admit it or not, The Public Enemy recognized that we all valorize the lives of gangsters.

The Public Enemy is out there to rent on Prime Video in the U.S.

Rent on Prime Video