Clint Eastwood Broke John Wayne’s Biggest Western Rule

The Big Picture

- John Wayne and Clint Eastwood embodied distinctive visions of American masculinity by way of their Western hero characters.

- Eastwood’s characters had a habit of shooting unsuspecting enemies, which contrasted sharply with Wayne’s refusal to shoot an individual behind their back in his films.

- The feud involving Wayne and Eastwood stemmed from their conflicting artistic sensibilities and interpretations of Western myth.

As the prominent faces of the Western genre and idealist representations of regular top males, it really is simple to examine John Wayne and Clint Eastwood to every other. Playing heroic archetypes of cowboys, law enforcement officers, and combat soldiers, Wayne and Eastwood defined a vision of American masculinity for various generations. Their artistic sensibilities place them in conversation with every other. Still, the two film stars differed in far more strategies than 1, particularly regarding their self-consciousness evoking a pristine image as heroes. Wayne portrayed dignified Western sheriffs with a proud sense of nobility, even though Eastwood’s postmodern take on the outlaw presented an uglier and nefarious underbelly of the Old West. The divide involving the two stars is exemplified by Wayne’s refusal to shoot an individual behind the back, but Eastwood is usually speedy with the trigger, even if his enemy combatant is caught off guard.

John Wayne and Clint Eastwood Played Very Different Western Heroes

An American icon from the Old West to the Vietnam War, John Wayne was a bigger-than-life figure. His films, notably with his prolific collaborator, John Ford, ostensibly represented American culture and history. While Ford’s greatest achievements as director, like The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, poetically deconstructed Western heroes as creations of mythmaking, Wayne separated art from himself in his private life. Unlike his contemporaries, he chose not to serve in World War II, and following this controversial choice, he adopted staunch conservative principles. He cooperated with the House of Un-American Activities (HUAC) throughout the 1950s to blackball alleged communists functioning in Hollywood, and he was speedy to label films as “un-American.” His gate-maintaining of appropriate American values on the large screen evolved into pure bigotry, as evidenced by his infamous 1971 Playboy interview.

Clint Eastwood, starting with his breakout into the mainstream with Sergio Leone‘s Dollars trilogy, deployed the greatest qualities of Wayne’s screen presence and matured his onscreen sentiments. Wayne, whose dramatic chops have been normally dismissed, excelled as a dramatic actor when stripped of his affectation of becoming the consummate All-American. In his roles as Ethan Edwards in The Searchers and Thomas Dunson in Howard Hawks‘ Red River, Wayne showed a far more cynical side to his heroism, as these characters fulfilled selfish desires involving years’ worth of pent-up bigotry and capital gains, respectively. With The Man With No Name, the titular lone ranger in The Outlaw Josey Wales, and William Munny in Unforgiven, Eastwood codified a character archetype discovered across various genres: the rogue outlaw, a killer with a suppressed heart of gold, and a clinical expert who talks sparsely. Westerns, in the wake of Eastwood’s revolutionary genre deconstruction, Unforgiven, have been anticipated to stick to anti-heroes with haunted souls.

Related

It Took Clint Eastwood Over 30 Years To Make This Neo-Western

Eastwood went back in the saddle 1 final time.

“When you have to shoot, shoot, don’t talk!” This astute Western logic supplied by Tuco (Eli Wallach) in Leone’s The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly served as the backbone to Eastwood’s Western characters. He seldom talked and fired his gun on instinct. Inspector Harry Callahan of the Dirty Harry series adopted a vigilante method to due procedure: shoot very first and ask concerns later. The speedy trigger of these characters saw no boundaries, even inside the unwritten guidelines of the Western genre. Not only did Eastwood’s outlaws shoot men and women unsuspectingly, he did not care if his opponent was drawing their gun. Due to their ominous names (such as the nameless “Preacher” in Pale Rider) and restricted quantity of dialogue, Eastwood carried an inscrutable screen presence. His conniving strategies cast a dark shadow on characters glorified as noble vigilantes. In Eastwood’s darkest films, like High Plains Drifter, his cowboys embody a satanic spirit cursed on society, and accurate evil sneaks up on you even though unguarded.

Unlike John Wayne, Clint Eastwood Would Shoot People Behind Their Back

The stark contrast involving John Wayne and Clint Eastwood is exemplified by an anecdote orated by Eastwood as a guest on Inside the Actor’s Studio. Host James Lipton noted that Leone’s Dollars trilogy shattered the black-and-white/superior versus evil conventions of the Western genre, evident by Eastwood’s nameless outlaw refusing to wait for his enemy combatant to draw their gun ahead of shooting. When describing the rationale behind shooting very first, Eastwood wryly asked, “It doesn’t make sense, why would you wait for somebody?” which drew a large laugh from the Actor’s Studio audience. Despite becoming the face of the contemporary Western, Eastwood analyzes the genre like a stand-up comic performing a routine mocking its illogical elements.

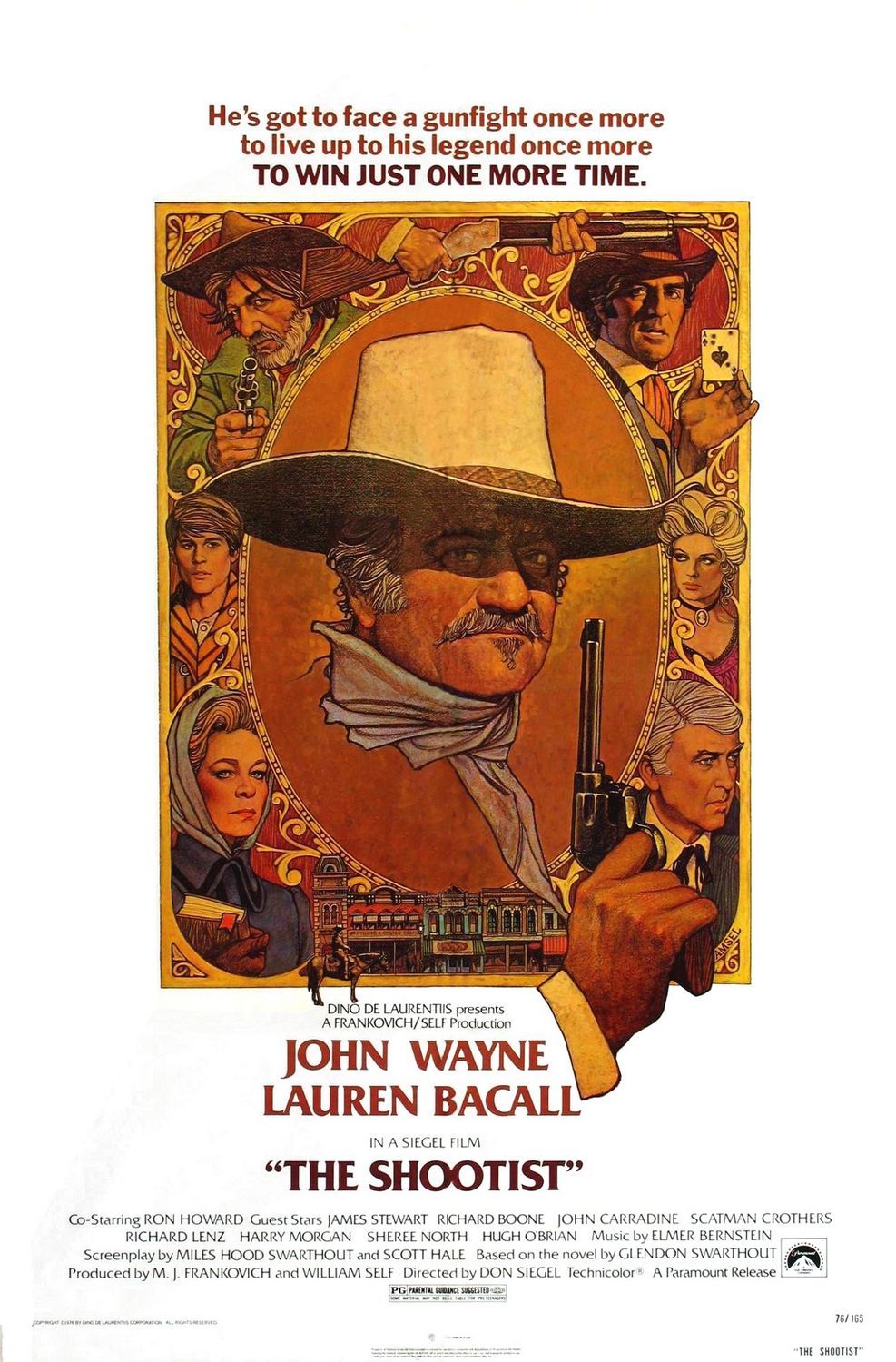

Eastwood then recalled a story he heard from Don Siegel, director of Dirty Harry and a handful of Eastwood films, who also served as a mentor for the actor’s foray into directing. In 1976, Siegel directed John Wayne in The Shootist, The Duke’s final film, which tracks a dying gunfighter as Wayne’s overall health was deteriorating in true life. When filming a scene exactly where Wayne sneaks up behind an enemy gunfighter, Siegel told him to shoot him. “‘You mean, I shoot him in the back?'” Eastwood recalled Wayne’s comments. “‘I don’t shoot anyone in the back,'” Wayne told Siegel. The director, as Eastwood place it, “made a terrible error,” by informing his star that Eastwood would have shot this particular person in the back. Needless to say, Wayne, a man of sanctimonious pride, was livid more than this comment. Eastwood, speaking in a broad impression of Wayne, stated, “‘I don’t care what that kid would have done. I won’t shoot him in the back!'”

The Drastic Differences Between John Wayne and Clint Eastwood Sparked a Feud

Despite their physical similarities, tall stature, intense gaze, and imposing physique language, Wayne and Eastwood’s artistic sensibilities differed. It’s not just that Wayne disagreed with Eastwood’s interpretation of the American frontier, he discovered his worldview an affront to his nation. In the ’70s, the two film cowboys engaged in a duel of their personal right after Wayne turned down a possibility to perform with Eastwood. Vehemently opposed to Eastwood’s vision, the Duke sent him a scathing letter critiquing High Plains Drifter. Eastwood cited the film, about a violent gunfighter hired to shield a town in peril, as a cautionary fable, but Wayne decried it as a treasonous text. Perhaps the film hit as well close to household for Wayne, as Eastwood’s nameless outlaw unflinchingly presented Western myth as a curse on society. In the film, the boundaries involving a noble vigilante and a ruthless savage are broken, as Eastwood’s character serves justice by way of violence, but the town loses all of its morality. Wayne, who constructed his profession off upholding patriotic values in the Western genre, could feasibly recognize the sobering reality that his roles represented.

Western outlaws and gunfighters are made to kill beyond the parameters of the law. Either way, regardless of whether they do it to their face or behind their back, murder is their calling card. While John Wayne opted to sanitize the depiction of cowboys, Clint Eastwood presented the raw truth of American folklore. His knack for portraying unfettered darkness in his characters created him the ultimate revisionist director — paying tribute to Wayne’s iconography even though expanding upon his messages for the contemporary era.

The Shootist is out there to stream on Paramount+ in the U.S.

Watch on Paramount+